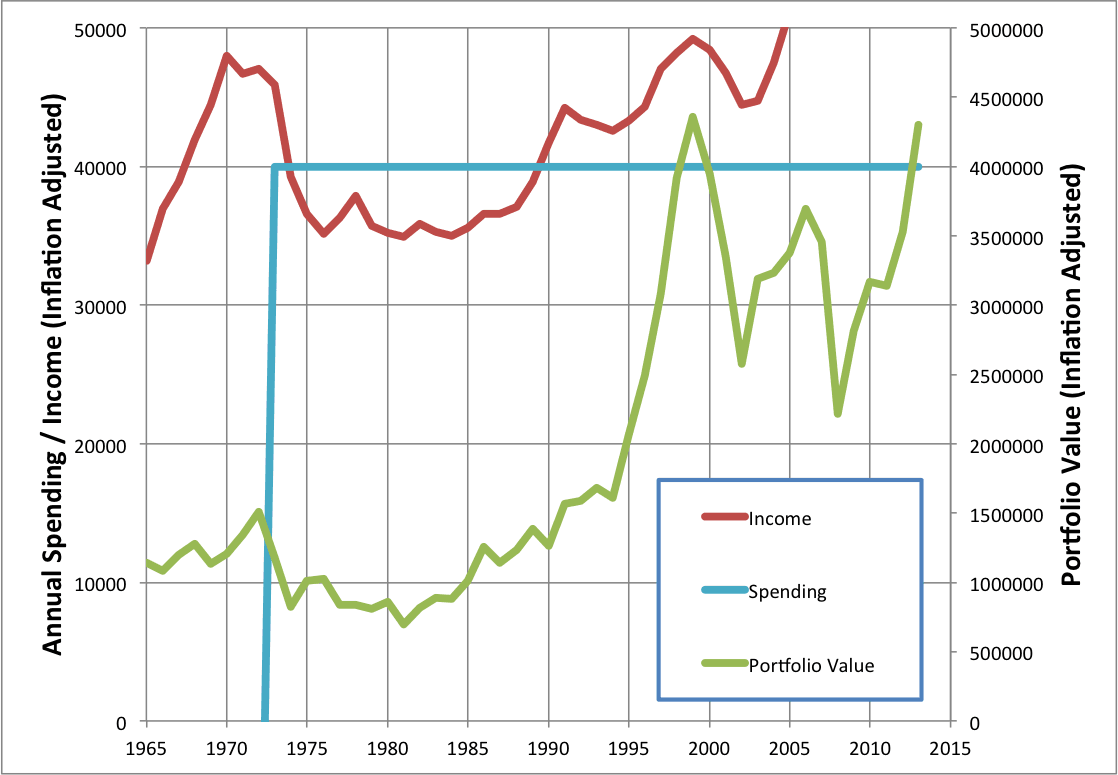

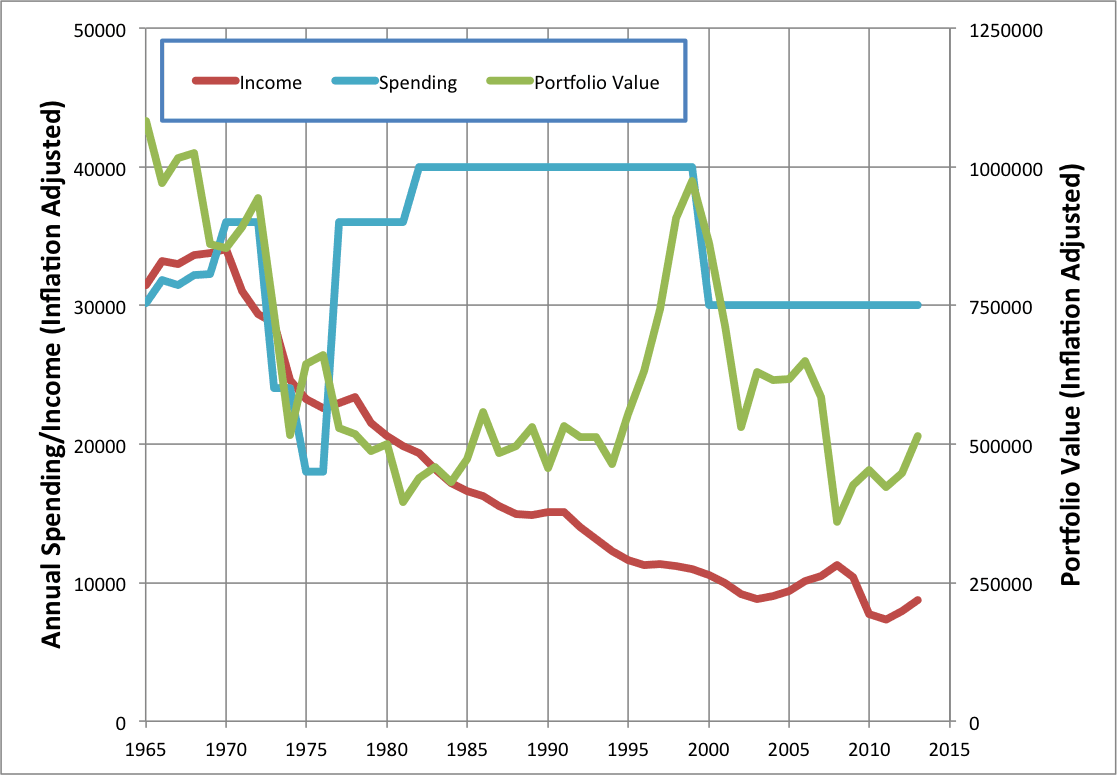

By living well below your means and investing in stocks and bonds, total assets have eclipsed $1 million, 25x your budgeted annual spending of $40k/year (all in 2014 inflation adjusted dollars, of course)

Everything you’ve read says that if you remain flexible, this should be enough to provide a relatively constant standard of living for the next 50 years, a must for somebody retiring in their mid 30s

The last few years at work have been a little stressful, so it will be nice to take time to recharge before diving into your new life’s ambitions… a little travel, learning a new language, writing a novel, communing with nature, creating music and art… all of the things that were put on hold due to the demands of career

People are a little confused on your last day of work. “But… what will you do all day?” “You are going to live off of your investments? I could never do that, the stock market is too risky” “How could you save so much, we can’t seem to save anything”

Your coworkers mean well, but their questions remind you of why you felt so compelled to gain freedom from the need to work in the first place. You walk out the door, a weight lifting off your shoulders for the first time in years

The Plan

It doesn’t take long to discover that early retirement agrees with you. Waking up without an alarm clock brings new meaning to the word luxury. With extra free time, exercising and making healthy meals at home feels natural. Riding a bicycle to the grocery store at 2 pm on a Wednesday is so much more enjoyable than the crazy after work rush, and it seems you can’t help but scratch items off your To Do list.

A few months go by, and as the stress of life melts away you start to feel like a new person. You finally feel ready to move on to bigger and better things

One of those things is a quick review of the retirement plan

With a 50+ year horizon, the portfolio is heavy on equities with 80% stock and 20% bonds, all invested in low-cost index funds. At the beginning we keep one year’s worth of spending in cash to help smooth out the inevitable bumps in the road. If there is a market crash early in retirement, we can move our bond position into stock and use the cash for spending

It seems a good time to depend on a portfolio instead of a job. The last few years, the economy has been quite robust. Inflation is low and growth is strong, and people seem optimistic about the future.

Our budgeted spending of $40,000 per year can provide for a high quality of life, more than we will probably spend (Although maybe we will spend that much someday.) Because the early years are critical to a portfolio’s long term survival, the plan is to spend a little less than 4% while we get used to our new life.

Is this plan sufficiently robust?

I hope so. We are about to retire in 1965, the worst year to retire Ever

(All numbers are 2014 Dollars. Using 1965 dollars, this fictitious retiree would have started with ~$135k and been spending ~$5.3k per year)

The First 10 Years

The first few years go by fairly smoothly. Income from dividends and interest grows and our spending grows with it. As during any time in history, bad things happen. In 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot. Vietnam War protests increase in frequency and intensity, including the tragedy that took place at Kent State. But good things happen as well. In 1969, the whole nation watched as Neil Armstrong stepped foot on the Moon, and it seemed anything was possible

But then President Nixon announces that the US Dollar can no longer be redeemed for gold, along with wage and price controls. This is going to take some time for the world economy to sort out, and there is nothing worse for the economy than the unknown. Even though our spending is still ramping up, we realize things will be turbulent for some time and are ready to make short term changes

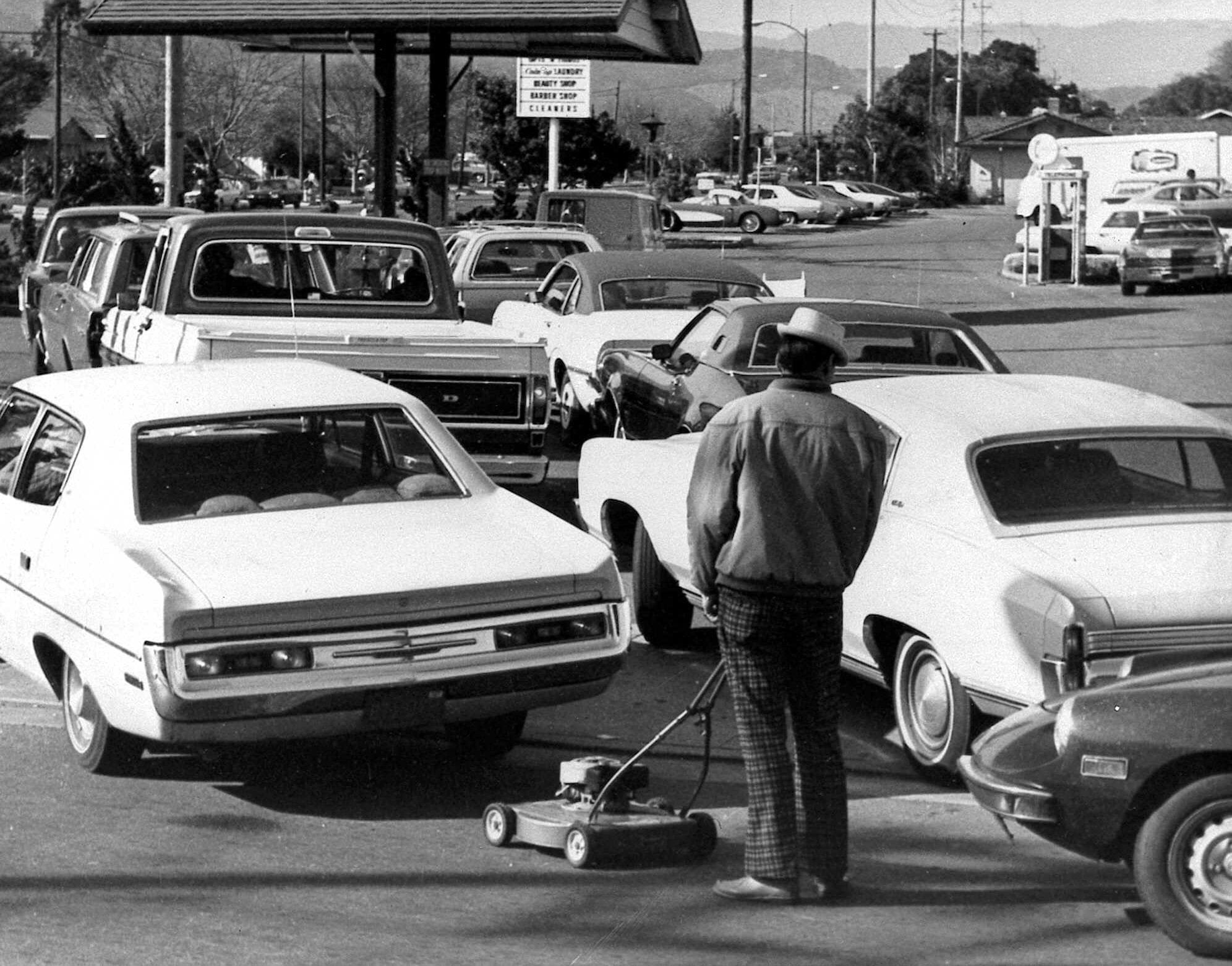

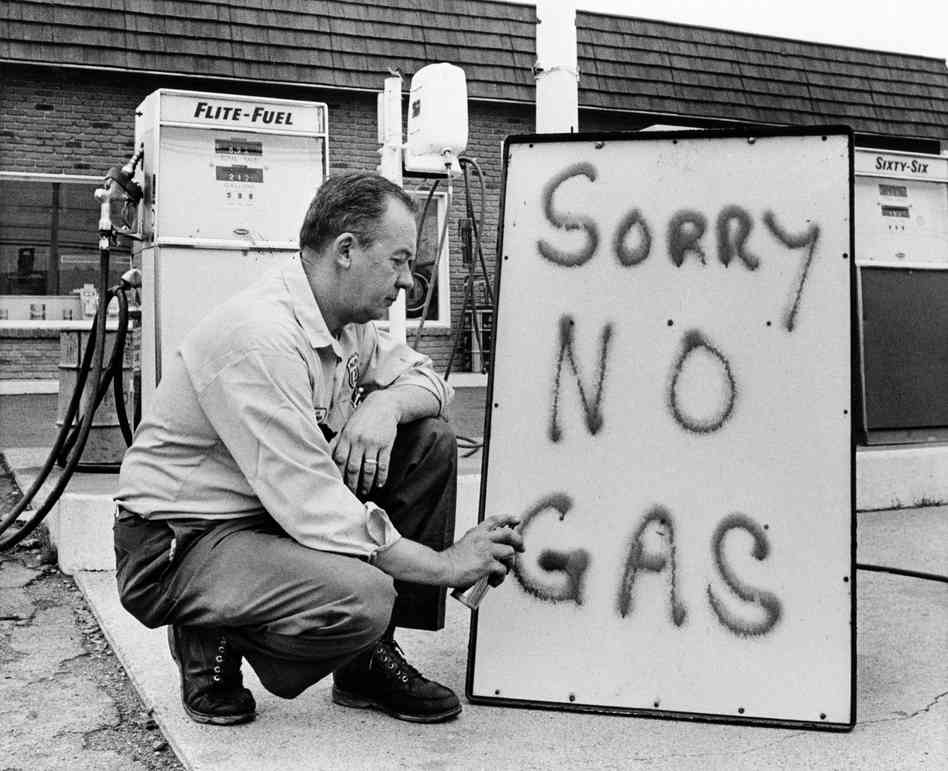

And then things get worse. In 1973 the Arab Oil Embargo causes oil prices to quadruple virtually overnight, pushing prices up on nearly everything. Price controls cause a shortage of gasoline, long lines, and fear

Worse than gas shortages and increasing prices is the plunging stock market. In 1973, the stock market drops 19%. In 1974, it drops another 25%. While inflation is kicking you in the gut, the stock market punches you in the throat

In what is one of the hardest financial decisions we ever make, we stick to the plan… moving half of our bond position into stock during our annual asset reallocation in ’73, and the other half in ’74. We go all in… 100% stocks. When the world looks to be on the edge of collapse, we fight that clenching feeling in our gut and follow the plan.

Touring all of the National Parks in an RV was part of the plan as well, but not with a gas shortage. Instead we prioritize our budget friendly goals and spend the next two years hiking the Appalachian Trail and biking across the United States. This helps drop our spending to about 2.5% of the initial portfolio value, less than we are earning in dividends

10 Years in daily life is quite enjoyable, but economically things are not looking good. The stock market has crashed, there is no oil, the President Nixon has just resigned, inflation is out of control, and when adjusted for inflation our portfolio is worth only half of what it was when we started

Making Adjustments

We would be hard pressed to find somebody at this point in an early retirement who wasn’t willing to make some adjustments to the plan

Inflation and unemployment have been rising steadily, and it is hard to predict what will happen next. Our own personal rate of inflation is much lower than the reported figures, but it is hard to ignore President Ford’s WIN speech and resulting drama

Maybe we can finish our book. That worked out well for that Harry Browne fellow with his success with How you can Profit from the coming devaluation

We’ve also had a few offers for some of the paintings we’ve done these past few years, maybe that could bring in some reliable income. Or the band we’ve been a part of could take on some gigs or busk on street corners, maybe even just for fun

But in the end, some friends have the idea of spending a year or two in Argentina and Brazil. Learning Spanish is on the Bucket List, and Portuguese sounds interesting as well. And we should be able to spend much less than just our dividend income in those countries. Let’s do it!

Two years later we return to the US, and things worsen. The Iranian Revolution causes another doubling of oil prices.

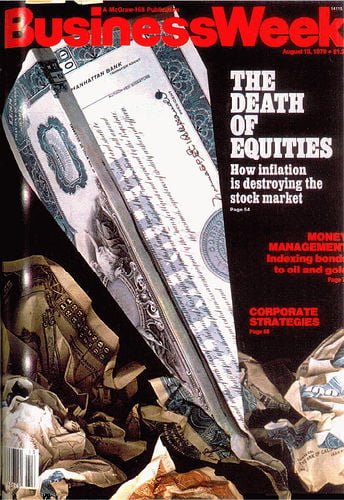

Paul Volker takes the helm of the Federal Reserve and makes policy changes to reign in inflation, causing a depression and a spike in unemployment. Things look so bad, Business Week predicts the Death of Equities

15 years into Retirement and our portfolio is still worth $500k (2014 dollars)

Maturing into Retirement

By now we’ve settled into our new life quite nicely. Some income opportunities present themselves regularly, but we always seem too busy to pursue them. Some years our investments do well, other years they don’t, but we are wiser (or perhaps just older) and the roller coaster doesn’t seem as interesting or exciting anymore

An upward surge in the stock market in the late 1990s makes us consider taking some money off the table, but we remember that market timing is a younger man’s game. Still, it is fun to see the portfolio return to its starting value on an inflation adjusted basis… even if just for a day

We start receiving Social Security income at Age 70. Income isn’t as high as it would have been had we worked an extra 30 years, but it is sufficient to cover 25% of our annual spending

Nearly 50 years later, our portfolio is still worth $500k. Our only source of income during this time was our investments. Looking back, we averaged a 3.7% withdrawal rate and lived a deeply rewarding life. The future looks equally bright

If this is the worst history has to offer, I’ll take it

Alternatives

Alternatives

A little flexibility goes a long way, and this retirement thought experiment has a happy ending. But what if we don’t want to be flexible? What if 4% withdrawals are a minimum?

Pure 4% withdrawals for a retirement starting in 1965 were a disaster, with the portfolio dropping to $0 in about 25 years. This occurred regardless of asset allocation. A portfolio of 50% stock / 50% bonds failed just as surely as a portfolio of 100% stock

But… if we were of the mindset that 3% was necessary, what we would have done in 1973? If in the first few months of retirement, the stock market dropped and the Oil Embargo began, would we have stayed the course? Or would we have returned to the work place? Safety first

What Made 1965 So Terrible?

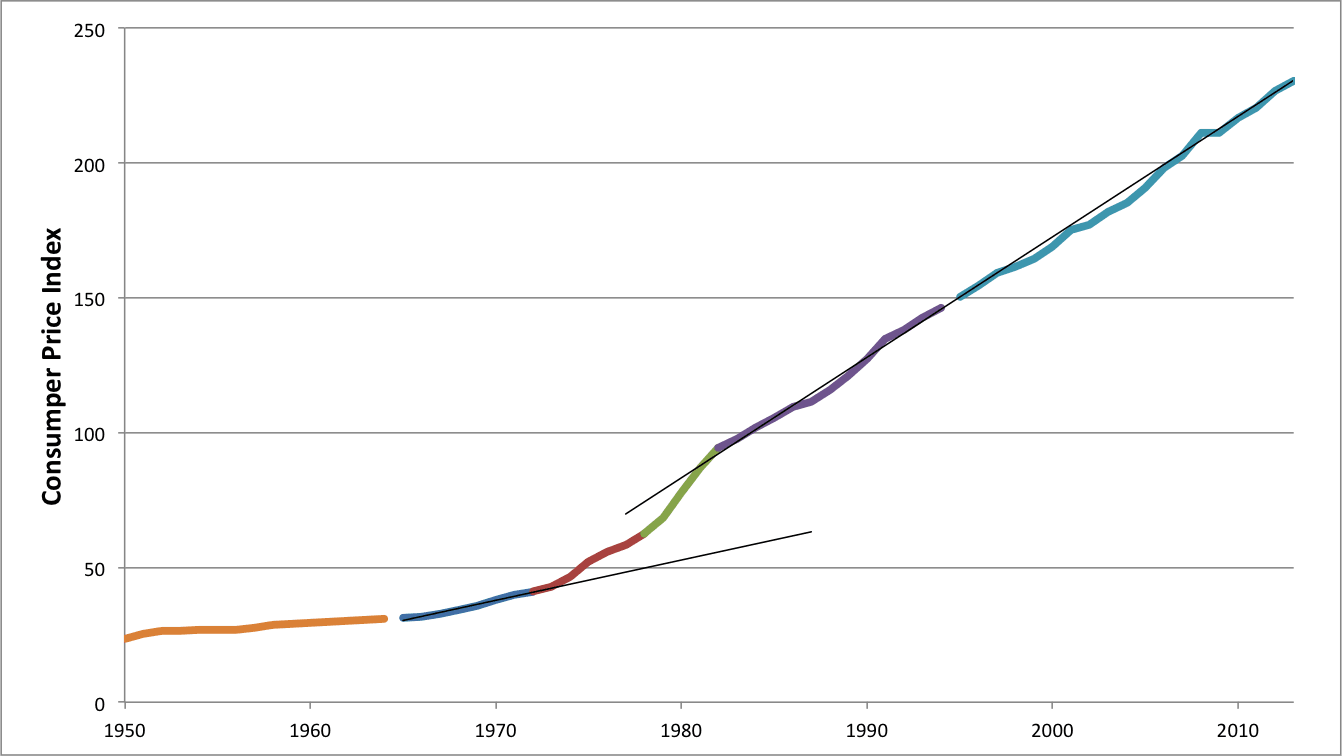

In the years after 1965, the perfect storm of retirement killing conditions took place. Inflation grew rapidly over the following decade, exceeding 10% in several years in the 1970’s and averaging 6% a year from 1965 to 1985. Interest rates rose rapidly, from ~4% in 1965 to ~8% in 1970, up to 15% in 1982, causing bonds prices to plummet. The combo of fast rising high inflation and rising interest rates destroyed bonds.

Stocks also performed horribly. Adjusted for inflation, the stock market didn’t rise above its 1965 value until 1992, 27 years later. Dividends moved sideways over 2 decades

But as we saw in our hypothetical 1965 retirement above, these things are manageable

The most insidious portfolio killer was inflation. When the stock market drops, we can’t help but notice. When interest rates are rising, we see the impact. But when prices increase, humans are horrible at internalizing the change

My grandfather used to complain about how expensive certain things had become, even though on an inflation adjusted basis they were actually cheaper.

Or consider how much excitement occurred when the Nasdaq recently eclipsed its 2000 high. But when including inflation, the Nasdaq is still 40% below the lofty heights of 15 years ago. The excitement is completely arbitrary

To understand the impact of inflation during this period, I looked at the CPI over the 60 year period before and after 1965. Inflation was largely predictable before 1965 and after the early 80s. However, the transition was painful. Between 1965 and 1982 prices would triple. The main contributions are generally agreed to be the result of closing the gold window, the Oil Shock, and discredited economic policies.

Since this was before my time, I asked the older and wiser Jim Collins to share his experience

While I lived thru them, I missed most of those sideways years, graduating from college in 1972 and starting my first professional job in 1974

I was pretty poor, especially living on 50% of my income so I’d have traveling money as I did. The point of this is that when you don’t have much, as long as you are employed, economic woes don’t much matter. While I was basically aware of the stock market, inflation and the oil embargo I didn’t have much skin in the game. Plus with inflation in play and being at the start of my career, I was able to double my income by 1978. With my low expenses I felt very comfortable. Without a car I never sat in one of those infamous gas lines.

I remember there was great fear built around inflation and it seemed destined to only worsen. And, of course, then as now, the talking heads were predicting disaster. The big difference, however, is there were far fewer and thus far less noise. No cable TV or internet.

Looking at stock performance during those years, you’ll notice that sideways motion started around 1965-6 and lasted until 1982. The market bumped between ~1000 and ~6-700 during those years. So the question isn’t so much why the 4% failed a couple of times, but why it held up as well as it did.

Conclusions

Reviewing all periods in the Trinity Study, the year 1965 was amongst the worst. While the future may provide even worse economic conditions, we can use this period to explore how strategies to improve portfolio longevity would have performed historically

By being flexible with spending, and being willing to adapt our goals to economic conditions, what at first appears to be a certain failure can become a long and rewarding retirement. In the worst of times, the difference between failure and success is small and largely within our control

I, for one, feel much more optimistic about our own retirement plans

See All of Your Accounts in One Place

Track your net worth, asset allocation, and portfolio performance with free financial tools from Personal Capital

That story is one of my worst fears, yet oddly reassuring. At least by being flexible, it still seems doable and you can ride it out. We have our budget set so that if something like that happened, we aren’t automatically forced to spend everything. Plus, having a pretty sweet 401k waiting for us at 60/62 is a nice light at the end of the tunnel if things get rough. I also have no issue if I need to get a part-time or even full-time job for a year or so if things go pear shaped.

Nice perspective reset with this read. Thanks!

You don’t include your 401k in your assets for planned spending before Age 60?

Yes and no. We know that if needed we can tap them using the Roth ladder or other means. However, all of our FIRE funds are in separate investments. We are assuming there is no help between when we quit our careers 3-4 years from now and 60 or so. No side income, which there almost certainly will be in some form, just “can our saved amount get us to 60 without working if need be?” That’s the number we’re targeting. Those funds will be close to depleted based on our simulations and assumptions by the time our 401k’s become available.

It is nice to stress test different scenarios out there. I always ask myself what could go wrong.. This is why I am reluctant to dip into principal in retirement planning – things could go wrong in a way that a model might not have predicted before. So having some margin of safety in retirement income is paramount.

I think that between 1966 – 1982, most of the returns came from dividends. So if you only spent those dividends ( starting yields were 3% in 1965), you would have done fine. The purchasing power was maintained in the initial years, but then dipped slightly by 20% or so by 1974 before slowly recovering its way.

This is the data behind what I am talking about. Sorry about posting outside link:

http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/datafile/spearn.htm

The other bad starting point would have been retiring at the end of 1999 with a very large allocation to US stocks. Stocks were overvalued, and off to delivering poor returns for say 12 years. And initial yields were low. I think inflation was manageable overall between 2000 – 2012 (though it seemed high in 2004 – 2007)

The absolute worst period would have been a Japanese Investor retiring in 1989 with say a high allocation to Japanese Stocks. Nikkei dropped by 50 – 75% within the first decade, dividend yields were low, P/Es were high. At least inflation was low.

Have you, or anyone tried to chart this using the Nikkei as a starting point? Just for a “worst case scenario” POV? It seems like the run up was slightly longer for the Nikkei and someone who started in 1980 might have been screwed if they wanted to retire in 1990. I am actually just starting to look into this situation myself to see what signs to be worried about.

I would just like to know if anyone has ever used a 100% Nikkei allocation to see what might happen when adjusting for inflation and dividend reinvestments. We are already 25 years in and they still haven’t recovered in nominal terms. However, it does look like they have recovered from a market cap perspective.

I’m not aware of anybody doing this specific analysis. You could look at some of Wade Pfau’s work, e.g.

https://retirementresearcher.com/20-year-sustainable-withdrawal-rates-for-us-and-japan/

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1699526

You could also possibly consider a 100% Pacific equities portfolio in Portfolio Charts, since Japan only data isn’t an option.

https://portfoliocharts.com/portfolio/withdrawal-rates/

I wouldn’t consider a Japan only portfolio as a reasonable comparison to an all US portfolio, but it might be a fun comparison nonetheless.

Thanks GCC. I wouldn’t really say it’s a relevant or reasonable case. I think there were things that should have made people wary of the Japanese market long before the crash, like extremely high P/E and a large population leaving the workforce. I think, from what I have read so far, that the Nikkei crash was more of an extreme combination of factors that is very unlikely to happen here. I just wanted to see the numbers to see what an outlier such as this might present.

I also found a thread on the boogleheads forum that had some pretty decent information on this and showed how different mixes would have lessened the blow.

Boogleheads thread if anyone is curious:

https://www.bogleheads.org/forum/viewtopic.php?f=10&t=23036&p=1979403&hilit=bpp+japan#p1971254

Anyway, thanks for the links. I think, like your story suggests, flexibility is always key to a longer term retirement.

“I think, from what I have read so far, that the Nikkei crash was more of an extreme combination of factors that is very unlikely to happen here.”

Could you say the same about the last 50 years of the dow jones? I think the US was likely an equally unlikely “extreme” but many of us are happy to base our investments on that one :)

I’ve always wondered what a retrospective of living through these different economic “crises” would look like as an early retiree. I mean, I get the abstract notion of flexibility. Live high on the hog (er, sushi and cheesecake) while times are good and tighten your belts and have refried beans con limon, tortillas, and carnitas when the times get tough.

But to see it fleshed out for 50 years is pretty cool. :)

Since history has a tendency to repeat itself, or at least rhyme from time to time, any 30-something early retiree should expect at least one sharp economic downturn during their retirement, and it might start today. Or in 10 years; no one knows. Be flexible in terms of spending. Be flexible in terms of earnings and don’t be afraid to monetize some hobbies or pick up a fun part time job if necessary. And you’ll probably be just fine whether you retire in 1928, 1965, or 2015.

I’m inclined to believe that an era such as 1965-1975 won’t happen again. The economic policies focusing on full employment with a rapidly increasing workforce (baby boom), the energy shortage, the ending of the gold standard, etc… are not likely to ever happen again (and the latter, impossible)

The problems of the future will probably be of the opposite variety… an abundance of cheap energy, a new normal of high unemployment (due to automation), declining populations in developed countries, climate change (no water in California), etc… Of course, everything being new just means we will all handle the mess just as poorly, and somebody will write a new The Worst Retirement Ever post in 50 or 60 years

It is OK though. We will remain flexible :)

After observing my inlaws retirement, I believe, I will always be open to some kind of work. I actually love my field and it has lots of flexibility with short term work and great locations. I do believe there may be circumstances that happen which make a retirement situation change, but having a backup plan always helps. My inlaws retired at 54 years (my Father In Law) and 62 years (my Mother In Law). However, after my MIL was retired for 4 months, she got bored. Then she went back to work within her field for 1 year, saving all of that money. Because they plan on doing another move and settle down in some small southern town, she needed the extra income.

There is probably data on this, but I wonder if the longer one works at a career, the less they are able to manage unstructured time in retirement. Little kids have no problem inventing elaborate worlds to play in. For adults, creativity seems to decline rapidly with lack of use

Great analysis. I hope this gives people comfort in retiring with a plan for 4% withdrawals rather than a more conservative figure — while understanding that if the economy falls apart, you may need to adjust course for a bit. The alternative to cutting spending down to 2.5%, as you suggest, is to cover that delta with earned income. In your $40k/year spending example, that’s only $15,000 per year of income required during the down years. Probably not a huge challenge for someone who has been financially successful enough to pursue early retirement.

Absolutely, I steered away from adding earned income in the analysis, but earning income is just the same as spending less (minus taxes) when it comes to portfolio longevity

Very cool case study for early retirement/financial independence! Interesting insights in how early retirement/financial independence would have worked at “the worst time” in history. Flexibility is key; but need to keep reminding myself of that on occasion. Would not mind the “move to south America for a couple of years” scenario, seems appealing.

Thanks for the good morning read, very encouraging.

I like the move to SA idea as well, although it could really be any lower cost of living location… SE Asia, Mexico, the US Midwest

We are just skipping the whole crisis incentive and doing the “outside the US / low cost of living countries” up front since the first 10 years are key

Such an interesting look at that part of economic history.

Inflation is the silent killer. However, with low overall costs (and this seems to be a near constant with early retirees) the actual dollar amount impact is somewhat muted. If my $300 grocery bill goes up 10%, that is certainly bad, but it’s also just $30. I can easily adjust that somehow, by eating less meat, or driving less, or whatever.

When we’re dealing with small numbers, the percentage increases can be balanced out more easily than with big numbers. Hooray for frugality.

True. And in many cases, frugality even decouples you from the economic system entirely

It doesn’t really matter what gas prices are if your preferred form of transportation is a bicycle

Jeremy, your analyses and write-ups are so consistently excellent that I’m going to stop prefacing my comments with the usual praise and just head straight to the relatively minor quibbles: in your tale of the 1965 early retiree, I think the almost-perfectly timed “market timing” move of shifting from bond to stock allocation in ’73 and ’74 is a bit unrealistic. If these early retirees were inclined to make such a move, I think it’s more likely to assume they would have done so at some point midway through one of the earlier (late ’60’s/early ’70’s) sharp drops rather than right at the VERY bottom in the mid-70’s (but even without running the numbers to confirm, I don’t think that would change the story significantly, which is why I view it as a mere quibble :) ).

I would have a quibble with that too. Ideally, the thought experiment would occur in a vacuum, but since I already know what happened…

That said, I used the same subjective criteria that I’ve followed in the past. I went “all in” the day the market opened after 9/11, and did the same over 2 stages in 2008. Although I missed the bottom in 2008, it still worked out well. I looked for a combination of mass hysteria and market declines, something that would have been the case in 1973/74 with the Oil Embargo, price controls, Nixon’s resignation, etc… Using annual data, I see only a 11% market decline in 1969, but a 19% decline in 1973 and a 25% decline in 1974

I also did asset reallocation only in December as part of normal asset allocation adjustments, so it wasn’t timed with the bottom

Had I actually lived through the late 60s / early 70s, perhaps I would have reacted differently. Fortunately, I did that analysis just in case

Starting with 100% stocks in 65 has similar results to the above analysis.

Holding 80% stock / 20% bonds throughout the whole 50 year period, or going “all in” in 1969, with all else held constant, then the portfolio fails in 2013 at the age of 83. Being similarly flexible with spending / income over the following years, with annual spending adjustments of at most 10%, then the portfolio has a similar terminal value of 500k

Which I suppose is a long winded way of saying “it wouldn’t change the story significantly”

Where have you talked about the all-in criteria? I’ve read most of your site and don’t recall it coming up. It smells, at first read, like market timing so I’d like to better understand it, especially in today’s environment.

Thank you.

It is market timing… or having some bonds is a way to have downside protection at day 1 (we started at ~90/10), but allows moving to higher equity concentration if valuations drop.

I don’t know that I’ve written about this explicitly – it’s mentioned in the summary of the 4% rule post, and then mentioned in this post (above) and in various comments around the site.

The alternative story could be going all-in a little early and after continued declines seeing that the remaining sum wasn’t able to cover even 3%, they sold all of it at the bottom in 1974 in order to preserve what little they still had.

As always, great stuff, sir. Though think you have a typo or a math error:

“Adjusted for inflation, the stock market didn’t rise above its 1965 value until 1992, 17 years later.” I think you meant 1982, if my memory serves correctly on timing, otherwise you meant 27 years. :)

all fixed now :)

Doesn’t sound like the worst retirement ever by far! The key is flexibility for sure.

Fantastic article. This is a great in depth look at what early retirement looks like through even the worst of times. Thanks again for this type of research.

Another wrinkle that could be added, would be what adding a stable rental property (or 3) to the mix does. It would make that portfolio even more stable.

Rental properties would have been great to own in 1965. Especially if the mortgages on those properties were really large. Having income triple and debt get cut by 67% in 10 years would make anyone rich

It would be cool if someone who actually was retired through that period commented, but Collins is probably as close as we’re going to get… The perspective that is missing are the details, like how hard it was to track stocks and bonds back then (probably had to call your broker to get quotes, and check the newspaper). Even more mind-blowing is that Bogle’s first ‘Index Investment Trust’ wasn’t created until December 31, 1975 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Index_fund).

The general message is a good one (although 1975 and 1976 would’ve had a lot of sleepless nights for me personally…), but I think that our generations have it much easier when it comes to retiring early!

In the current age, ER is substantially easier than at any time in history. Income / hour worked is higher than for agricultural or physical labor eras, access to low cost investments is completely democratized, as is the information on how and why.

As negatives, access to debt is more prevalent and more likely to be abused, traditional education is priced too high, and advertising and media have set expectations artificially high

I would have liked to talk with somebody who had retired in the mid-60’s, but Jim is the oldest financially responsible person I know :)

While not an early retiree, My great uncle retired from John Deere in 1965 at the age of 56. He spent the next 40+ years Salmon fishing in Alaska, British Columbia, and Oregon. He lived frugally, and when he died at the age of 100, he had millions of dollars left.

That’s an awesome little story :)

Awesome timing on this article. I spent a number of hours this weekend reading blog and forum posts on the failure scenarios, sequence of return risk, the importance of the first 5-10 years, and most importantly as you have highlighted, being flexible. Some folks are figuring out how to know when the time to be flexible is, any thoughts on that?

I’ve used a proprietary GCC algorithm

For the case of increasing allocation of stocks, I’ve done this in the past when there is both mass hysteria and a large market decline. Mass and Large are subject to interpretation. Twice in life I was really lazy about investing and had too much cash, and this criteria applied. Once was the day the market opened after 9/11, the other was in 2008

For spending, any time the economy is officially in recession would be a good time to spend less. If the economy is in recession and the stock market is down significantly (inflation adjusted) then that would be a good time to hike the Appalachian Trail

Unless you are thrown another curve ball at the same time, such a major medical expense. Flexibility goes out the door at that point. Better have those deductible and max out of pocket amounts covered in your annual expense calculations.

I don’t think it is necessary to cover those expenses in your budget, assuming they are one time expenses. If you are undergoing cancer treatment, odds are you aren’t also vacationing in Paris. If one year you need to spend $50k instead of $40k due to health issues, and it also happens to be in a down market, etc… then it requires more flexibility later

One could also make the logical leap that if you are undergoing cancer treatments, or the like, you have a lower probability of making it another 10-20… years to worry about how-where your portfolio is going. Morbid, I know. Just food for thought.

Alright I get the first part, the second part I’m assuming is probably an easy answer, but information that I don’t currently have. So, how do I really know when we’re in a recession? I think the term is thrown around all the time in the media with little consensus. And then how do you calculate whether the market is down adjusted for inflation?

This is hard to say. It might be a case of you know it when you see it

If you were living in Greece right now, and there is 25% youth unemployment and everybody is talking about your country defaulting and maybe leaving the EU…

In 2008, billion dollar insurance and investing companies went bankrupt overnight, GM was going to have to shut their doors and layoff 200k people, etc…

In 1973, oil prices quadrupled and there were shortages of gas, inflation was 10%+ and there was a panic about it

In 1929, there were runs on banks, etc…

This general theme of economic disfunction is difficult to miss, even if these examples are the extremes

One good place to look at official numbers for inflation, unemployment, etc.. without having to watch the news is Robert Shiller’s site

http://www.multpl.com/

Great post GCC! Interesting to see one approach to ER with a 80/20 split and plotted across a difficult time line.

Jeremy:

It is time to carve your mug next to Jim Collins’ on the Mount Rushmore of FI. Your posts, particularly of late, have been of the highest quality. Something tells me the immient arrival of GCCJr. has given you laser like focus and resolve. :) What I find fascinating about the era described above is the ushering in of double digit return rates on CDs. Can we go back to those?! Excellent retrospective analysis.

Think interest rates can’t go negative?

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2015-04-23/largest-bank-america-joins-war-cash

Did somebody say interest rates can’t go negative? I missed that

I didn’t read the linked post, because the first sentence implied a rant was to follow

But, interest rates certainly can go negative. Some might say they are today, especially when taxes are included. Or in the example of some Swiss banks charging some people to hold cash

Having a 12% CD seems nice but if inflation is 10% and you pay tax on the full amount of interest at a marginal rate of 25%, in practice you earned -1% on that money

haha, thanks Jon. The last few posts have been the result of sleepless nights and being in a constant daze. GCCjr was born 4/11, and everything has been in slow motion / auto-pilot ever since

Hey – is little GoCurryCookie here yet?

Born April 11th

Congratulations on your boy Jeremy & Winnie! Wish him that he is as smart as his parents, plus healthy, wealthy, and wise!

I know in some cultures, the son is expected to look after their parents when they get older. So you have additional margin of safety for your retirement years ;-)

Thank you DGI

Depending on GCCjr is now an official part of our safety margin :)

Wow what a cute kid! And enjoyed the article to the nth degree.

April is a good month. My son just turned 8, and a real great friend of ours has her birthday on the 11th :)

Awww, love it! :D

Hoorah! And well done Jeremy and Winnie! Thanks for sharing a photo of the little angel.

Congratulations Jeremy and Winnie! This is a joy like no other.

Another excellent post. It’s a nice reminder that flexibility is the real key to a successful early retirement. Shoot for 4%, but stay flexible. I have to admit, I was wondering where you were going with that title after reading the first several paragraphs. Well played.

That’s why it’s such a a good idea to eliminate all debt from your life if possible. The less you have to pay, the better off you are in terms of preserving your nest egg. We paid all everything in 2013 and are looking fwd to retiring before 40.

Thanks for posting this. What an excellent piece of reference material. Like many early retiree hopefuls, I have run and re-run my numbers through cfiresim and that pesky 1965 keeps popping up as the failure – although other times in the 1960’s aren’t far behind. It is wonderful to see someone take the time to explain what happened and why small adjustments could have made the difference.

I have to agree with the comment from Jon, above, in that you are really making significant contributions to the FI community. Thanks and keep up the good work!

Thanks Prob8!

cFIREsim results are exactly why I dug deeper. It is pretty easy to say be flexible or spend less in a down market, but I wanted to try to experience it as much as is possible, even if only as a thought experiment

Great article Jeremy! I always enjoy your posts when they pop-up in my inbox and this one is definitely a favourite. It is getting Jo and I increasingly inspired and excited for our own plans, although we may be a little way off taking the step in to retirement just yet. Plans are afoot!

Thanks Rich. Yeah, plans! Are you and Jo still in Australia?

We are indeed! We’ve recently arrived and settled in Melbourne. I’ve got a job here starting full time next week so we plan on being for some time! Hope all is well in Taipei with the new arrival :)

Hi Jeremy this is a nice take. It seems based on my variable withdrawal research the 2 problematic periods are in 1937 and 1969. But hindsight is a bitch. Its another experience to lived through one.

Kitces seem to think having that initial cash allocation is not really that helpful.

At the end of the day its good we build up a bigger sum smalller withdrawal rate, but most of the time we are doing variable withdrawal.

The 4% act for planning but FI folks do not spend based on Bengen’s assumptions and stipulations. And that is my critique of it.

This is an interesting article, but I’m troubled by the mixing of current dollars vs. historical dollars. If someone were to retire in 1965 on $40K/yr, that would translate to almost $300K/yr now. And if you said you had $1M in 1965, that would be like having $7.3M now. I don’t think most of us would be surprised to think a person could retire on $7.3M, or manage to live on $300K/yr!

Everything is done in inflation adjusted dollars, consistent with cFIREsim output

It may be worth adding a note of what their original starting portfolio amount and annual spending amount was (and then note that it’s equivalent to 40k/1MM today, and was consistent throughout). Inflation tends to screw with people’s heads. :D

I added this to the end of the post

$1 million in 2014 dollars is approximately $135k in 1965 dollars

$40k annual spending in 2014 would be similar to $5.3k/year in 1965

Thanks for this. Great data and I appreciate this post.

A nice write up! I just want to caution that flexibility isn’t necessarily as readily available at the very moment you need it because that’s when everybody else is also scrambling. The part-time job you want to get becomes super-competitive. You don’t even get offers for retail or fast food jobs because they have tons of experienced folks to choose from. Is flexibility a different way of saying doing something you didn’t choose in the first place? In that regard, the frugal types are at a disadvantage because they are already frugal. If there’s a chance that you will compete for part-time retail or fast food jobs, working one more year in your own profession before you quit will be 10 times more effective.

Excellent points Harry

I used a lot of our own plan in this thought experiment, so I don’t think of flexibility as doing something we didn’t choose in the first place. I want to drive an RV around the US, spend time in Argentina and Brazil, and to hike the Appalachian Trail. But all the items on the Bucket List are time independent, so if gas prices quadruple we can do the RV trip later

A more curmudgeonly type might view these changes as a huge inconvenience. That’s how I felt about working one more year

I really wish I had read this (and lived my it) 18 years ago when I started military service.

This is one of the most interesting PF posts I’ve ever read GCC. I read it twice, just to let it sink in and think about the applications. Fascinating look at the importance of being flexible and responsive to what the market is doing. Our plan is to simply be flexible and if we need part time work to cover expenses in a down market, then we’ll do that. Great examples of adapting one’s retirement activities to the market as well, i.e., hike the AT or head to Latin America.

This is brilliant!!!

Nothing more to add. Great thought experiment and very well written and explained.

Thanks

Congratulations! It is a live changing and humbling event having a child. We had two daughters years ago and can just imagine what you are going through now.

I just recently found your site 3 months ago and I am first time commenter. I really love your posts and have read every one of them! :)

I find it fascinating to hear stories about people attempting to and actually leave the rat race. You have proven that by your passive income, location independence, and a mobile lifestyle. It seems to me that the common theme is that we get to a point that we are sick and tired of the status quo, we start to align ourselves to a big goal, we save and/or start a side hustle to finance this goal, and then we ultimately jump in with both feet. We have to find a better way.

My wife and I struggle with this last step of leaving our jobs behind. Financially we can do it now but we just seem to think we need to wait just a little bit longer. I noticed one of your posts talked about waiting many extra years to pull the trigger. We are working on that fear of leaving our steady paychecks and believe we will be in the same spot as you and your family by next year.

Hi Bryan, thank you for reading and for your kind comment

Congrats on your success. Waiting longer is a perfectly reasonable thing to do. With life expectancy in the eighties or more, what is one more year? It isn’t really a competition, and there are no bonus prizes for retiring earlier than anybody else or on a schedule

I probably worked 3 years too long, but life is great either way.

I’d be interested in seeing the results of a floating 4% withdrawal (Ie: When portfolio is at 1,000,000, you withdraw 4% ($40,000), when portfolio is at 500,000 you withdraw 4% ($20,000)).

This way your portfolio would never fall to $0, and you would take out slightly less in the bad years, and (on average) spend a far more appropriate amount over the (good) years (avoiding ending up dying with millions never spent!).

You can experiment with many different types of withdrawal methods using http://www.cfiresim.com

I assume this is the same Chris that replied to me above with this:

“Could you say the same about the last 50 years of the dow jones? I think the US was likely an equally unlikely “extreme” but many of us are happy to base our investments on that one ”

If not, sorry. I was just trying to reply to you but it wouldn’t let me above because of it’s distance down the reply chain.

Anyway, to answer your question. I don’t know that you could say the same for the SP/Dow. P/E went fairly nutty before 2008 – But we have corrected since then. We are trending back up near 25, which (to me) is another leading indicator the bull might be slowing considering the fact that the historical average is 16. That and the fact that the SP saw nearly no growth last year. I know we have had growth to date this year, but as has been noted, you can’t really predict a crash.

P/E sources:

http://www.multpl.com/

http://siblisresearch.com/data/japan-shiller-pe-cape/

I think, based on my reading, that corporate debt could be a problem in coming years, but again, that’s wait and see. Fortunately for me, I’m near the beginning of my accumulation phase, so I have the least amount to lose on risk. Also, nothing I state should be taken as fact, given that I don’t have a degree in economics (although I do find it very interesting), nor am I any source of authority on any of these matters. I am merely making correlations that may not actually exist. I just find this stuff interesting.

Another read on corporate debt.

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/09/government-debt-isnt-the-problemprivate-debt-is/379865/

You thoughts on the article by Dr. Wade Pfau http://www.fa-mag.com/news/why-4–could-fail-22881.html?section=47&page=2 ?

Assume that future returns will be worse than historical returns, just because, and then slip in a 1% expense ratio for a financial adviser to manage your funds, and it will fail

I’m late to the party, but I’d also would like to state that this is a great piece and gives a sense on how it would be to retire in on of the worst possible years.

However there are two things about this piece that puzzle me a bit and this is regarding reconciling the graph at https://i2.wp.com/www.gocurrycracker.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/RetireIn65FlexiblePlan.png with the text:

1. The text state that the plan is to spend a bit below 4%, yet the graph starts the spending rate at 3%. Is this due to the savings buffer or why?

2. According to the text the spending drops to about 2.5% of the initial portfolio around 1975, yet in the graph the spending drops below $20k, which is less than 2%, if your starting portfolio has eclipsed $1M. From the graph I’m guessing that the starting portfolio is about $1.1M and the spending drops to $18k, so that’s more like 1.6% to 1.7%, not 2.5%.

So what am I missing?

1. 3% is less than 4%. Sequence of returns risk is one of the biggest risks for portfolio longevity, which can be reduced by spending less. We did this by starting to travel in Latin America vs Western Europe.

2. Dunno, maybe I meant something else or maybe I did the math wrong. When the market craps the bed, precision isn’t the most important thing. Spend less is the moral of the story. We would pursue do so by hanging out in Guatemala or Thailand, or by doing some long distance hikes.

I feel like we are living in a similar situation now in 2022, what do you think?.

I think it is important to understand why you feel that way. Maybe we are, maybe we aren’t.

Gas shortages? No.

Price controls? No.

Only vehicles available get 10 mpg? No.

Gold window closing? No.

Inflation? Yes

Bond yields rising? Yes

Stock market down? Yes.

I expect we are not in similar times. We have a supply shock as a result of turning the economy off and back on again (like an old, cold fluorescent light tube.) It will turn on fully at some point.

Such a great post to put things in perspective. I’ve been retired since early 2019 and yet I still enjoyed maintaining some of my self employment work. As a result of still working, I haven’t touched my portfolio at all. The assets have gone up so much that even if it was cut in half I would still have more than I needed to live on at a 3.5% withdrawal rate.

I’m somewhat immune to the inflation, I don’t drive my electric car all that much. I’m a vegetarian. I own my own house and am not impacted by inflationary rent. I don’t travel a whole lot.

This is a post I come back to from time to time for exactly that perspective.